Just over 18 months ago, Nasdaq introduced its green equity designations for its Nordic stock markets. The designations were a set of operational and reporting standards, that if met, would confer a so-called Nasdaq Green Equity designation. This in turn would, could or should carry weight with investors, institutional and retail, who, in light of all the interest in ESG investing, were presumably looking for companies that met the standards of their mandate.

Adam Kostyál, Head of European Listings notes Nasdaq is not in the green ratings business nor does it intend to be. Rather, he says, it’s a participant in a global effort to develop a set of green equity standards that issuers and investors can coalesce around. The task is no less monumental than getting companies to report toward agreed-upon accounting standards. But one day, hopefully, green equity standards will be as relied upon GAAP or IFRS accounting standards are. Therefore a look at Nasdaq’s nascent efforts offers a window on the greening of the capital markets at large.

Early Entrants

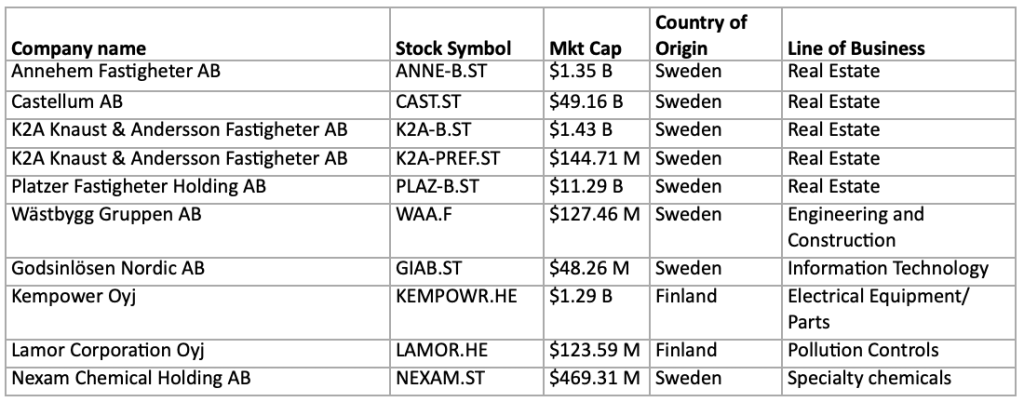

So far, 10 companies have met the standards of Nasdaq’s green equity designation says Kostyál. He anticipates 10 more designations in 2023. The current designees are shown in the table below.

Nasdaq Green Equity Designees

Among the 50,000 or so companies that come under the purview of the European Commission, 10 companies are not a lot. The low number is driven by the rigor of the Nasdaq’s qualifications standards and uncertainty among issuers about the benefits of the green equity designation. There are no studies to confirm the reticence of issuers to seek a green equity designation. However, the ratio of action to inaction is perhaps all the study one needs. As for the rigor of Nasdaq’s green equity standards, that’s as it should be perhaps. At a broad brush level, Nasdaq doesn’t want to aid and abet issuers in greenwashing their operations.

Slow, But Steady?

The slow uptake in green equity designations is curious in light of the rapid uptake in ESG-driven mandates faced by pensions, endowments and other funds. Logically, these asset managers would gravitate toward marketplaces that have done some of their homework for them and create a demand for green equity designations, and this demand would pull through applications for a green equity designation. But this does not appear to be the case yet.

Nasdaq’s standards themselves delve into four principal areas which include “turnover” of operations toward sustainable activities, the nature of CAPEX investments, alignment with EU Taxonomy, which is a classification system for sustainable activities, and the establishment of environmental targets.

This taxonomy alignment is far-reaching. Starting January 2023, EU corporate reporting requirements will require companies to be transparent on their alignment with the EU Taxonomy and might well increase the rate of green equity applications. After all, disclosing alignment is a large step companies would need to take anyway if they are seeking a green equity designation. With much of the heavy lifting a regulatory requirement, it’s not hard to imagine issuers would take the next steps to get a green equity designation.

The EU taxonomy came from the EU Taxonomy Climate Delegated Act and was created to support sustainable investing by making it clearer which economic activities most contribute to meeting the EU’s environmental objectives. This transparency will require material changes in how internal resources are organized to comply with these reporting requirements.

Still, it’s easy to imagine issuers will be cautious in their approach toward alignment with EU taxonomy. While the aims are noble, the publication of adherence to a taxonomy or a forecast regarding environmental targets can open the company to legal and regulatory exposure as well as unfavorable investor reactions. And for issuers whose stock enjoys a good level of liquidity, and upon which financing solutions, and the long-term viability of the company rests, why rock the boat?

Power Players

The Nasdaq green equity designation requires a third-party review conducted by Shades of Green and Moody’s ESG. Shades of Green which was developed by CICERO, a Norwegian climate institute, was purchased by S&P in December of 2022. S&P and Moody’s presence on the scene demonstrates there is real analytical power behind the emerging green equity designation. For both of these firms, issuing ratings is close to their core business. Moreover, it’s possible to imagine that green designations could someday rival their other ratings businesses.

Moody’s and S&P’s Shades of Green already have robust businesses in green bond ratings. With some $4.5 trillion of social bonds outstanding, up from $1.5 trillion two years ago, there’s plenty of debt to rate. And unlike the green equity business, the green bond rating business is straightforward. Either a bond-financed project is green or it’s not.

Equity is more complex. And in this regard, while Moody’s and Shades of Green’s bond businesses can actually drive growth, the equity business might be characterized as a business still in the laboratory.

In truth, however, there may be no other choice but to incubate. In the words of Nasdaq’s Kostyál, “It’s not about our standard, but about setting a standard. If you let the market set the standard, it will take a much longer time but it will be more effective than a standard that is forced upon the marketplace.”

This article was first published on Nasdaq.com. To see this and other articles by David Evanson, click here.