For 20 years, the executives at JGWPT Holdings, LLC, and its subsidiary and predecessor companies (collectively, JGWPT) have focused almost exclusively on structured settlement payment streams. Structured settlement payments-their nuances, how to buy them, underwrite them, and how to structure the cash flows to back bonds for institutional investors—have been major focus points.

The words “structured settlements” and “structured settlement payment streams” are

new to many. The concept of using the cash flows that come from them to back bonds is probably even newer. This article should provide the reader with an introduction to structured settlements, structured settlement payments, and the bonds we issue backed by their cash flows. With it, investors can explore this burgeoning asset class and perhaps find new opportunities that provide stable cash flows with uncorrelated risks.

BACKGROUND

First, what is a structured settlement?

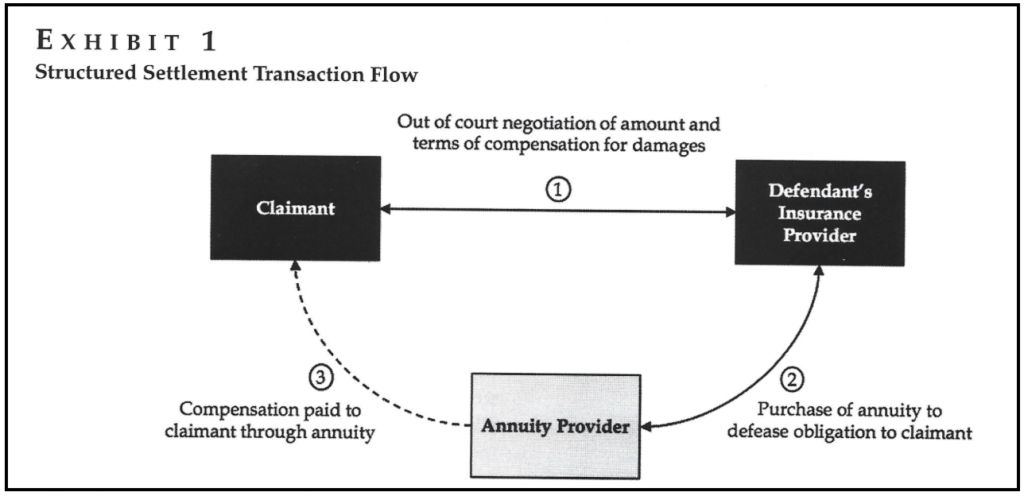

The term refers to a broad category of financial resolutions between an aggrieved party and a party deemed to be responsible (or their insurer). In a structured settlement, often used to settle wrongful death and personal injury cases, the plaintiff is paid money over time, rather than in a single lump sum, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.

Structured Settlements Come to Prominence in the United States

Structured settlements are believed to have originated in Canada. Following the widespread prescription of Thalidomide in the 1960s to help ease the symptoms of morning sickness, it was found that the drug caused deformities in the fetus. As a result, the plaintiffs in the cases sought a settlement that would provide financial benefits over the lifetimes of the affected population, which was expected to be 70 or 80 years, far greater than the life expectancies of their parents.

The ultimate settlement of the case used annuities, which are simply contracts issued by insurance companies that guarantee future payments in exchange for the payment of an immediate premium. By purchasing annuities, the defendants’ insurance companies could guarantee that plaintiffs would be paid financial benefits well into the future.

During the 1970s, structured settlements were increasingly used in the United States to settle personal injury and wrongful death suits due to a variety of factors:

- An overall increase in personal injury awards;

- High levels of inflation meant that insurance companies could reduce the cost of settlements by paying them over long periods of time, in effect using deflated future dollars to settle current claims;

- IRS rulings waived federal income tax liabilities on structured settlement payments.

Although the notion of making payments over time as a way to reach settlement may be intuitively obvious, the purchase of an annuity to fund this obligation may be new and striking. By using an annuity, however, the defendant’s insurance company can reduce the cost of the settlement. After all, it is paying the present value of future payments, which is less than the summation of the payments.

Moreover, the existence of annuities to fund structured settlements is the single lynchpin upon which factoring of payments makes sense and gives rise to the possibility of bonds backed by their cash flows.

VAST MARKETS

It’s important to understand that because litigation is a growth industry in the United States, the number of structured settlements is vast. By several estimates, the dollar amount of structured settlements in place is about $100 billion. Moreover, each year approximately $4 billion to $5 billion in new settlements are added.

The Source of Personal Injuries and Wrongful Death

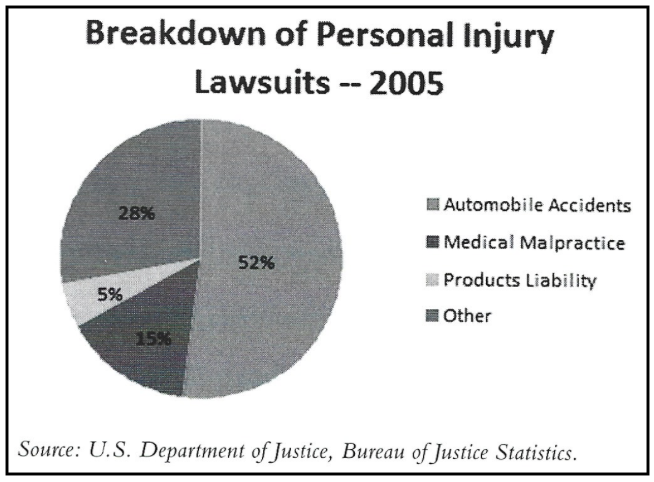

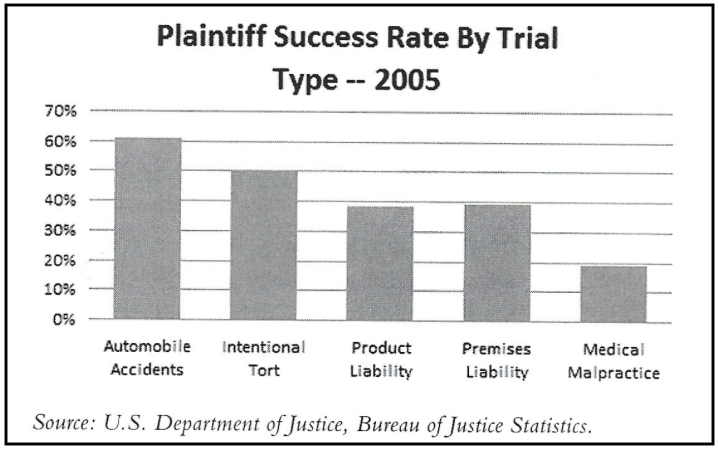

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, approximately 31 million injuries to people throughout the United States each year require the care of a doctor. Of these, nearly 2 million require hospitalization. Annually, about 162,000 people die from their injuries. The pie chart indicates the various sources of the injuries.

The circumstances surrounding each injury are unique, even, generally speaking, for injuries within the same category. For instance, there are more than five million automobile accidents each year. In some of these the injured party was driving. In others, the injured party was parked and unaware of the impending danger.

Some injuries were caused by drunk drivers, others by uninsured, or under-aged drivers.

Given this diversity of circumstance, the structured settlements provided to plaintiffs tend to be diverse as well.

In truth, only 4% of personal injury cases ever go to trial. A large number reach a settlement before a trial1. Thus the size of the structured settlement market is validated not simply because attorneys find settlements expedient but also because structured settlements deliver real benefits to both the plaintiff and the defendant’s insurance company.

Specifically, the benefits for the plaintiff include the following:

- Future costs that may be borne-such as medical, housing, education, as well as occupational or physical therapy—can be anticipated and funded by the arrival of future payments.

- When appropriately designed, structured settlements reduce the plaintiff’s tax liabilities and in most cases are tax free.

- By settling a case with a structured settlement, plaintiffs can avoid the time, expense, and uncertainty of a trial and jury award. In cases where injuries require immediate and lengthy medical treatment or the death of a spouse has created an immediate need for income, a settlement may be more expedient than spending years in court.

- Structured settlements can protect plaintiffs from inappropriate spending or depletion of their awards, which can leave them unable to pay for future costs associated with their injury.

For the insurer, the primary benefit is that the total cost of the settlement may be lower as future payment obligations, by virtue of inflation, can be paid with less expensive dollars. In addition, the insurer reduces the legal expenses of prolonged litigation, which are paid in current dollars.

There are, however, disadvantages to structured settlements for some plaintiffs:

- Some people can manage money very effectively and can earn a return on a lump sum settlement with widely available investment products that will exceed the implied return of the annuities used in structured settlements.

- The plaintiff’s life may change in ways the settlement did not anticipate, making the stream of future payments at odds with the plaintiff’s actual needs.

- Structured settlements cannot be turned into cash quickly. The proceeds from a lump sum settlement can be held in cash or stocks, bonds, and mutual funds that can be converted into cash very quickly to meet unexpected opportunities or expenses.

These last two disadvantages of structured settlements conspired to create the secondary market for structured settlement payments. JGWPT, through its two independent and competing brands “JG Wentworth” and “Peachtree,” is by most accounts the leading secondary market participant; JGWPT has purchased over $8 billion of future payment obligations from consumers.

CREATING ANNUITY-BACKED ASSETS

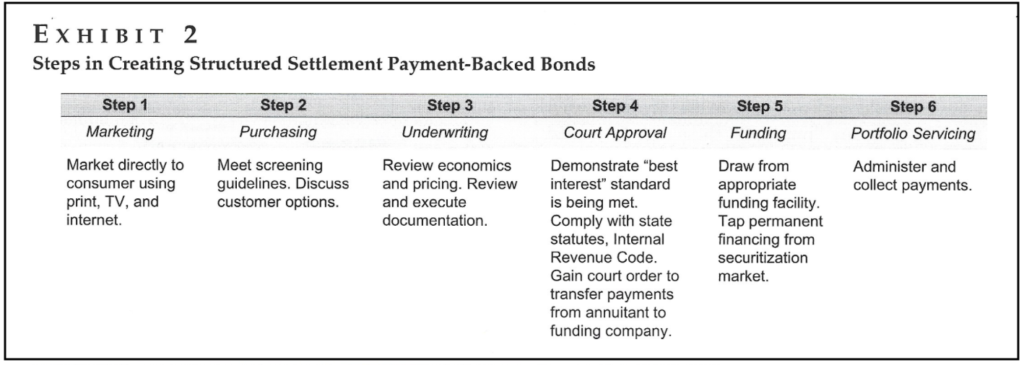

Exhibit 2 shows the steps in creating structured settlement payment backed bonds. All steps in the process are vital, but steps three and four-underwriting and court approval-bear more discussion as they relate to the structured finance market and opportunities for fixed-income investors.

Consistent underwriting standards and approval by a judge through a court order are key factors to evaluate when looking at a structured settlement payment stream.

Initially, when two parties enter into a structured settlement agreement, there is no need for a court order, but when that payment stream gets transferred through a subsequent change, it requires the approval of a judge. The standard that must be met in making these changes soften termed “best interest.” Specifically, is the sale of future payments in exchange for a lump sum in the “best interest” of the individual?

Do Structured Settlements Work as Intended?

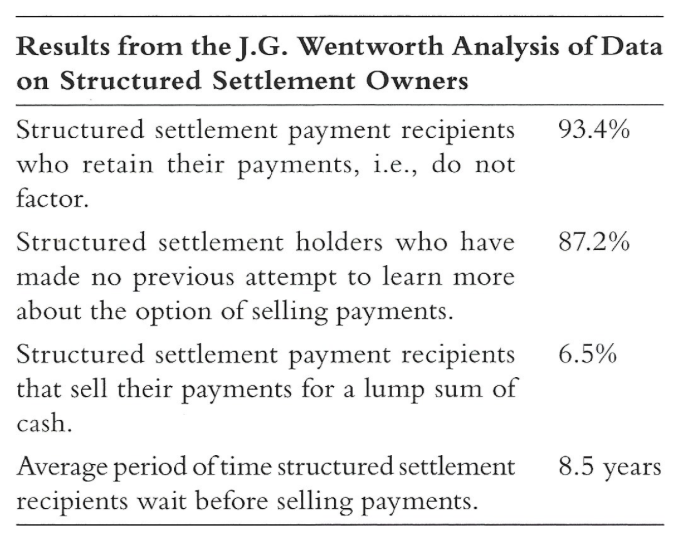

Structured settlements are one of the most important and successful legal tools devised. Testimony to this is the high rate of retention among individuals with structured settlements. According to a study conducted by JGWPT using 20 years of data collected on individuals with structured settlements, 93.4% maintain their payment streams as originally devised. The remaining structured settlement owners sell some or all of their payments for a lump sum of cash.

Although there is a small secondary market in which structured settlement owners can sell their payments, our study found that 87.2% of structured settlement holders have made no previous attempt to learn more about the option of selling payments. Of those individuals who sell some or all of their payments, they waited on average 8.5 years before they sold any portion of their settlement payments.

There are several implications issuing from the need to attain a court order, both positive and negative.

- The process of selling payments is substantially lengthened. Filing a petition, gaining a court date, and getting the customer to successfully walk through their day in court can take weeks or even months. This timeframe can create frustration and hardship.

- Court orders are generally issued at the county level and there are some 5,500 county jurisdictions, each with its own idiosyncrasies.

- Judges can and do deny petitions resulting in dissatisfied customers.

By far, however, the most important byproduct of obtaining a court order to transfer payments from the individual to the funding company is the unassailable right of the funding company to receive these payments. Should the payments be misdirected in the future by subterfuge on the part of customers or administrative errors on the part of the annuity issuer, the funding company has recourse and an avenue of redress to recoup money owed to them.

The importance of this feature cannot be understated. It factors largely into the default experience with these assets. In this sense, enabling the court order process to be successfully completed is one of the important ways the funding company “improves” these cash flows and reduces the risks that investors face buying fixed-income securities backed by structured settlement cash flows.

REDUCING RISK

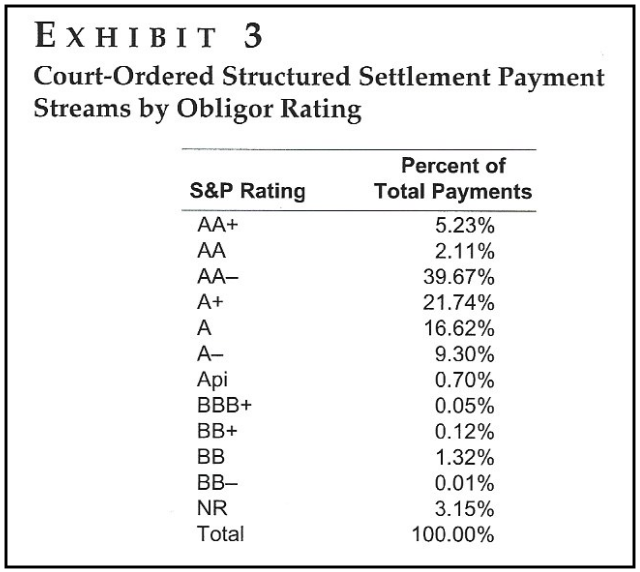

In addition, by obtaining a court-ordered right to receive regular payments from the annuity issuer (the obligor), in a specified dollar amount, for a specified period of time, the funding company fundamentally changes the quality of the receivables. That is, the payments evolve from being unrated, private cash flows into rated ones based on the rating the annuity issuer is assigned by various rating agencies.

Exhibit 3 shows a sample pool of structured settlement payments organized by the obligor’s Standard & Poor’s rating from an issuance of structured settlement backed notes that was completed in July 2012 by subsidiaries of JGWPT. A distribution of Moody’s ratings shows similar results. Note that approximately 94% of the pool is backed by insurance companies rated A or better.

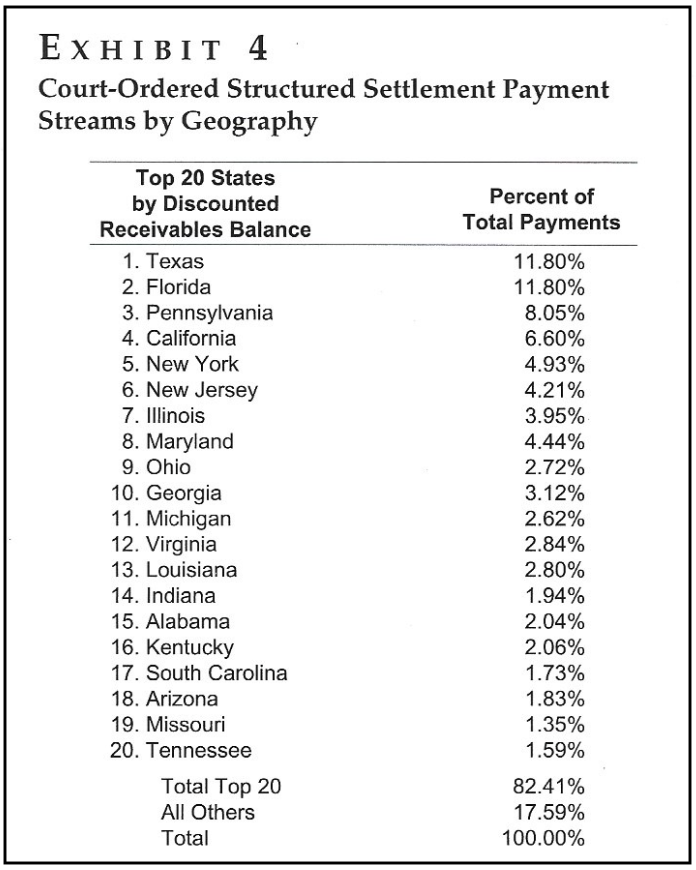

The cash flows from structured settlements are also diversified by obligor with the top 20 obligors representing just over 80% of the pool. And finally, the cash flows from structured settlements of the pool are diversified by geography, as shown in Exhibit 4.

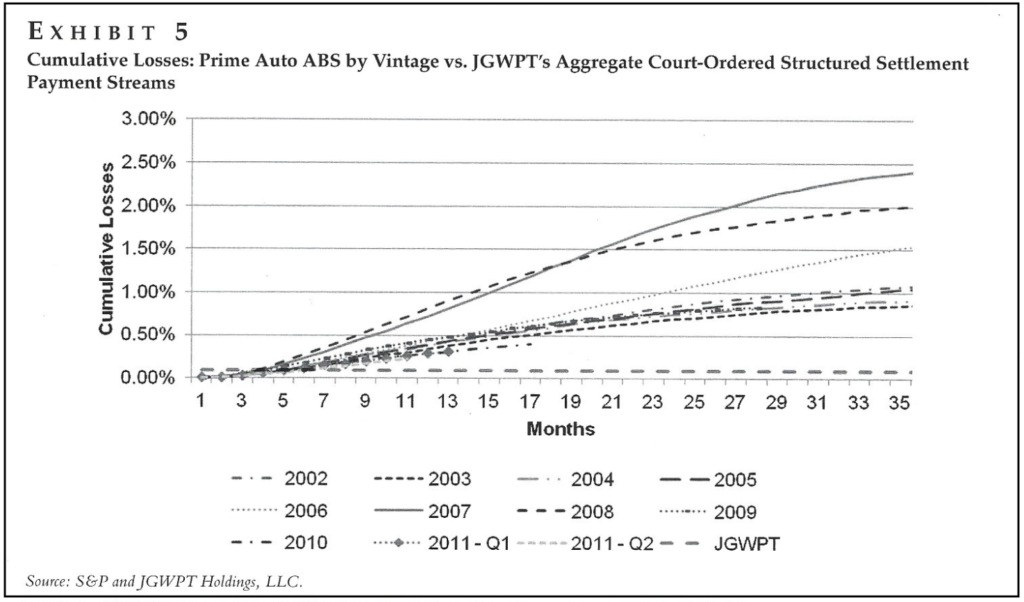

Of course, the proof is in the numbers. Exhibit 5 shows the default rate on cash flows from court-ordered structured settlement payment streams versus prime auto asset-backed securities. The GWPT loss rate on $4.4 billion of assets across 48,000 separate receivables is the dashed horizontal line showing a cumulative loss rate of 0.088%. Exhibit 5 shows that JGWPT’s court-ordered structured settlement payment streams have outperformed prime auto asset-backed securities on a cumulative loss basis.

Risk is multi-dimensional. It’s not just default risk that a fixed-income investor faces. There’s interest rate, prepayment, and economic risk too. As many fixed-income investors will likely remember:

- The sharp decline in oil prices between 1980 and 1985 and then again from 1990 to 2000 created what amounted to a regional recession in states tied to petroleum production. Everything – from residential real estate prices to commercial leasing to auto loans and leases— was affected.

RISK CONTROL OPPORTUNITIES

In July 2012, JGWPT issued its 33rd securitization consisting of two issued classes of notes: 1) $144 million of Class A notes rated Aaa(sf) by Moody’s Investors Service and AAA(sf) by DBRS and 2) $13.9 million of Class B notes rated Baa2(sf) by Moody’s Investors Service and BBB (high) by DBRS. A third tranche, retained by JGWPT, consisted of $11.4 million of notes.

The tranching of structured settlement payment backed bonds provides investors with important risk management tools. The so-called “Retained Class” of notes held by the issuer is simply an overcollateralization that serves as added cushion to absorb the losses that might occur during the life of the notes and which is based on historical loss experience. This $11.4 million Retained Class tranche represents an overcollateralization based on JGWPT’s loss rate to date.

The Class B notes, which absorb any losses incurred beyond the $11.4 million of Retained Class of notes, is intended to provide investors with a 6.77% fixed coupon.

The $13.8 million tranche of Class B notes represented 8.25% of the recent offering.

The Class A notes, which are protected from losses by the Class B notes and the Retained Class of notes, is intended to provide investors with a 3.84% fixed coupon.

The $144 million tranche of Class A notes represented 85% of the recent offering.

The Class A and Class B notes are further protected and enhanced through a 1% reserve account that is set up on day one of the transaction.

JGWPT’s regular issuance program and predictable cash flows have been instrumental in expanding our investor base. In fact, investor interest for ABS deals backed by structured settlement payments has seen a steady increase over the years, from just a handful five years ago to more than 30 regular institutional investors who actively invest in the asset class today.

JGWPT was the first specialty finance firm to securitize structured settlement receivables starting in 1996 and today is the largest and most prolific securitizer of these assets. As a pioneer in the purchase of structured settlement payment streams, JGWPT participated in the industry prior to regulation. From that point, JGWPT was a driving force behind the development of the market through regulation at the Federal and State level.

ENDNOTE

1S.A. Terry. “The Cost of Pursuing a Legal Claim.” Legal Finance Journal, August 26, 2011.