KPMG CECL Survey 2018

Preface

In order to gain added insights into the current state of CECL implementation, KPMG surveyed over 100 financial institutions. Survey results reveal that progress has been made, but consistent with last year’s results, companies are still struggling to make certain critical accounting, modeling, and data decisions. Here are the issues proving to be the most challenging:

- Determining the length of reasonable and supportable forecast periods

- Establishing the manner in which to revert to historical losses after the reasonable and supportable forecast period

- Defining reasonably expected troubled debt restructurings

- Determining the life for CECL measurement of certain financial assets (e.g., credit cards)

“The large number of decisions that still need to be made by financial institutions was our key finding,” according to John Lyons, Director, KPMG’s Accounting Advisory Services. “Larger institutions must now decide whether to throw human and financial capital at their CECL implementations in order to be able to start their parallel runs in quarter one of 2019 or whether to push back the start date of their parallel run to later in 2019.”

In assessing which course of action is best, Lyons says, “There is no one right answer, but, in general, we would suggest that smaller institutions, those with assets of less than $50 billion, are likely to be better suited to delaying the start of their parallel runs to the second quarter of 2019 because they are less likely to suffer untoward consequences from a shorter parallel run than larger institutions. Moreover, smaller institutions are less likely to have the human and financial capital on hand to compress the remaining decision making into the remaining months of 2018 and early 2019.”

Methodology

KPMG surveyed 107 financial services institutions in August 2018, including 82 banks, 21 insurers, and 19 specialty finance companies (noting that some entities selected more than one classification where appropriate). The asset sizes of these institutions were broken into four buckets: less than $10 billion in assets, $10 billion to $50 billion in assets, $50 billion to $200 billion in assets, and more than $200 billion in assets. A variety of professionals participated in the survey, including C-suite executives, vice presidents, controllers, and treasurers.

Accounting

| At this point, implementation teams need to prioritize the making of certain decisions and identify how and when the parallel run process will proceed. In some cases, a lack of decision making to date may even put the start of parallel runs in early 2019 at risk. |

During the implementation of IFRS 9, we observed significant decision-making paralysis that pressured deadlines and threatened implementation success. While CECL and IFRS 9 implementations are qualitatively different, some of the dynamics are similar, such as the large number of business units involved in the change.

Those tackling CECL should be aware that decisions need to be analyzed properly, but key decisions cannot be delayed. Additionally, it may be necessary to prioritize certain decisions that must be made to commence parallel run while allowing other decisions to be influenced by early parallel run results. Identifying the prioritization and timing of decisions, then, becomes a key element of the implementation plan.

The current survey indicates that companies are still struggling to make key accounting decisions. These delays will come home to roost very shortly. That is, the expectation among upper management at larger financial institutions that CECL implementations will enjoy a full year of parallel runs will come face to face with the fact that the models have not been built, in part because many accounting decisions remain outstanding. In certain industries, such as insurance, the delays in decision making are even more pronounced.

At this point, CECL steering committees need to communicate a stark message—make certain key decisions by early 2019 or push back the start date for parallel runs.

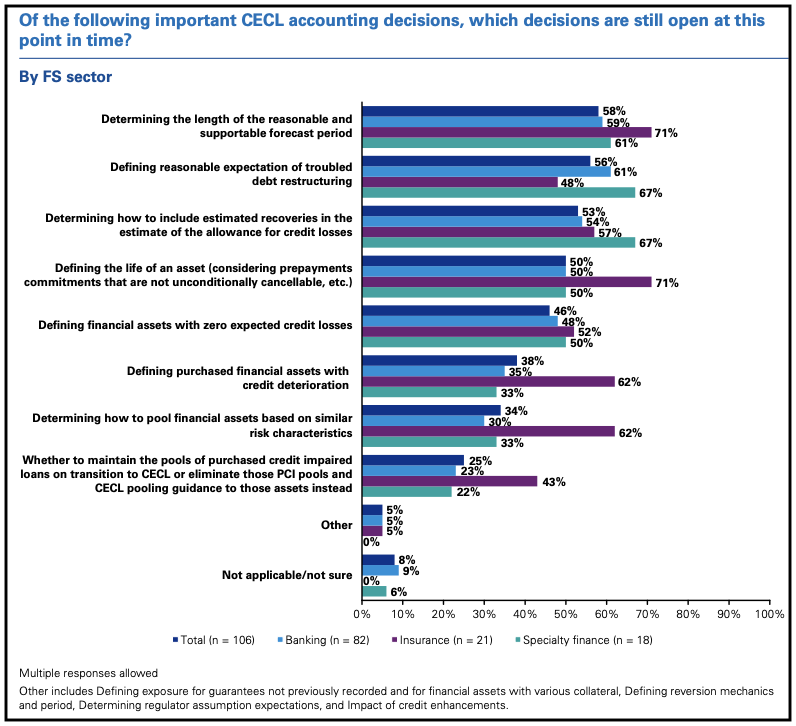

Half of all companies had still not decided how to define the life of an asset. Both this year and last year, one third of all companies were still debating how to pool financial assets with similar risk characteristics. These are certainly decisions that need to be made in order to begin the parallel run process.

Moreover, as implementation nears, companies have failed to decide on many other critical issues. Over 50 percent of companies have failed to make decisions on the following, a number of which are accounting related:

- Defining reasonable expectation of a troubled debt restructuring

- Determining how to include estimated recoveries in the estimate of the allowance for credit losses

- Defining financial assets with zero expected credit losses.

Certain other judgments, such as determining the length of the reasonable and supportable forecasting period, may be considered during the parallel run phase, and, in fact, the related decision making could be an expected outcome of the parallel run. Others, such as how to include estimated recoveries in the CECL estimate, are more fundamental to the modeling process and lack of decision making may delay the parallel run.

The importance of tackling these issues cannot be understated. At its core, CECL relies on models, and models require both credit risk and accounting decisions. CECL makes it especially challenging to make decisions since the standard permits a multitude of approaches, and there is no one predominate approach on items ranging from the length of reasonable and supportable forecast periods to estimating prepayments, to pooling financial assets, among other items.

Surprisingly, approximately one-fifth of institutions had yet to identify commitments where unfunded credit commitments are unconditionally cancelable. Among this group, the greatest uncertainty existed concerning the following asset types: construction loans, revolving loans, HELOCs, commercial mortgage loans, and credit facilities not fully committed. Generally speaking, across all institutions—banks, insurance companies, and specialty finance companies—the uncertainty regarding unfunded amounts was lower among large institutions (i.e., greater than $200 billion).

The difficulty banks face in making key decisions concerning unfunded commitments is interesting because a similar analysis is required under the Basel III standard, with which many banks are already complying. The large number of over $200 billion institutions that had not identified unfunded amounts that were unconditionally cancelable may indicate CECL steering committees have not connected yet with the other areas of the organization doing the same or similar work and which ultimately will need to be brought into the CECL implementation efforts.

Modeling

| Certain modeling decisions must be made prior to commencement of parallel run activities, while other decisions may be influenced by early parallel run results and modified accordingly. |

We asked questions about several aspects of modeling and found, similar to our questions concerning accounting and data, that respondents still had choices to make. These are described in more detail below. However, the absence of decisiveness in general highlights the central conflict of CECL implementation as 2018 comes to a close. Specifically, financial institutions must prioritize decision making by resolving those decisions that are critical to commencement of parallel run or risk pushing back the start date. At this point, there are early warning signs that some institutions may end up with an abbreviated parallel run period. Organizations should come to terms with this reality and tailor their expectations accordingly.

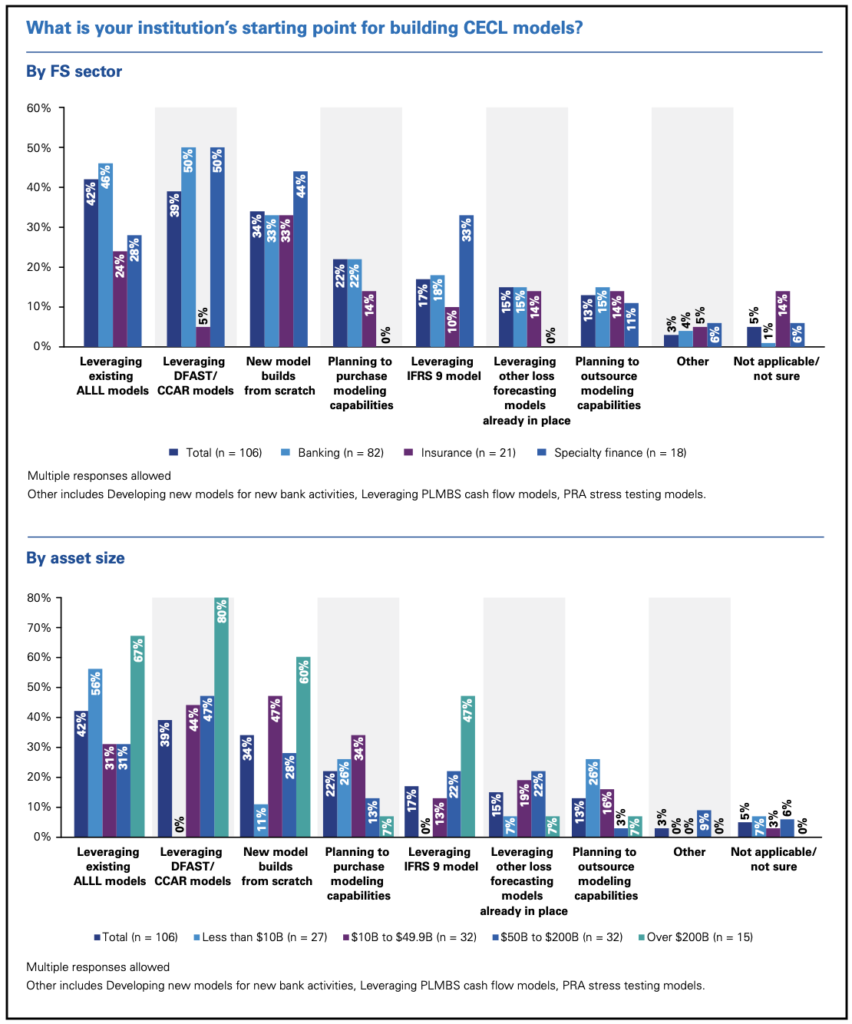

Last year, 32 percent of institutions said they intended to leverage their Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test (DFAST) and Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) models as a starting point for building CECL models. This year, 39 percent intended to do so. While this may be a good starting point, these existing models may not be well suited for the purpose of CECL loss estimation. CCAR and DFAST focus on the adequacy of capital and the ability of banks to withstand economic stress based on scenarios provided by regulators. In contrast, credit loss estimates under CECL are intended to reflect management’s best estimate of expected future credit losses by adjusting historical loss experience for current economic conditions and reasonable and supportable forecasts.

Fewer institutions said that they will rely on Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL) models as a starting point for CECL models this year versus last year (42 percent in 2018 and 52 percent in 2017). It is therefore not surprising that more companies are planning to build models from scratch this year (34 percent) than last year (24 percent). In our opinion, existing ALLL and other loss forecasting models may provide a useful starting point for CECL modeling, particularly for smaller institutions, but still require careful consideration to determine which modifications are needed to conform with CECL’s forward-looking loss measurement principles for estimating future credit losses.

| At this point, there are early warning signs that some institutions may end up with an abbreviated parallel run period. Organizations should come to terms with this reality and tailor their expectations accordingly. |

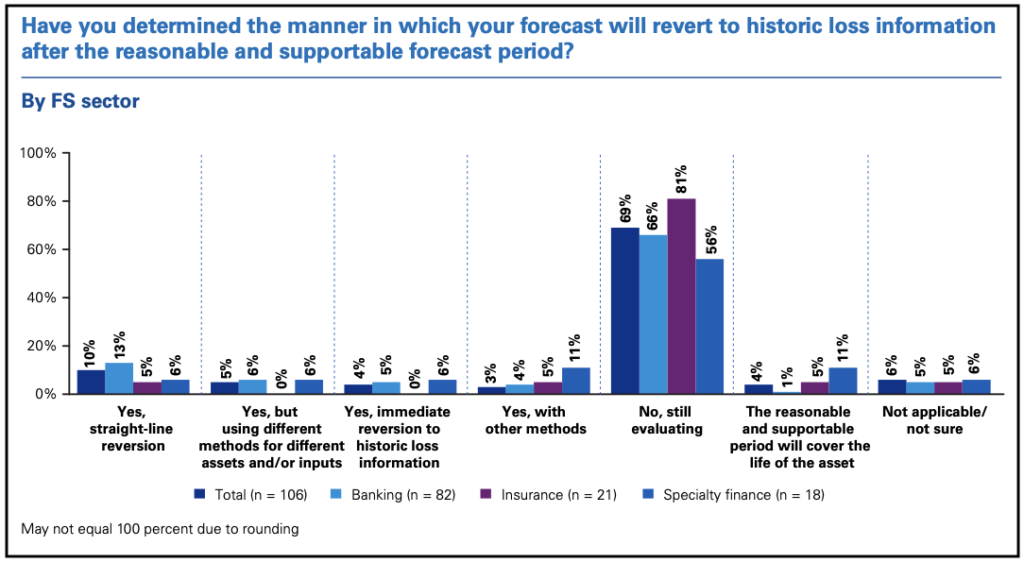

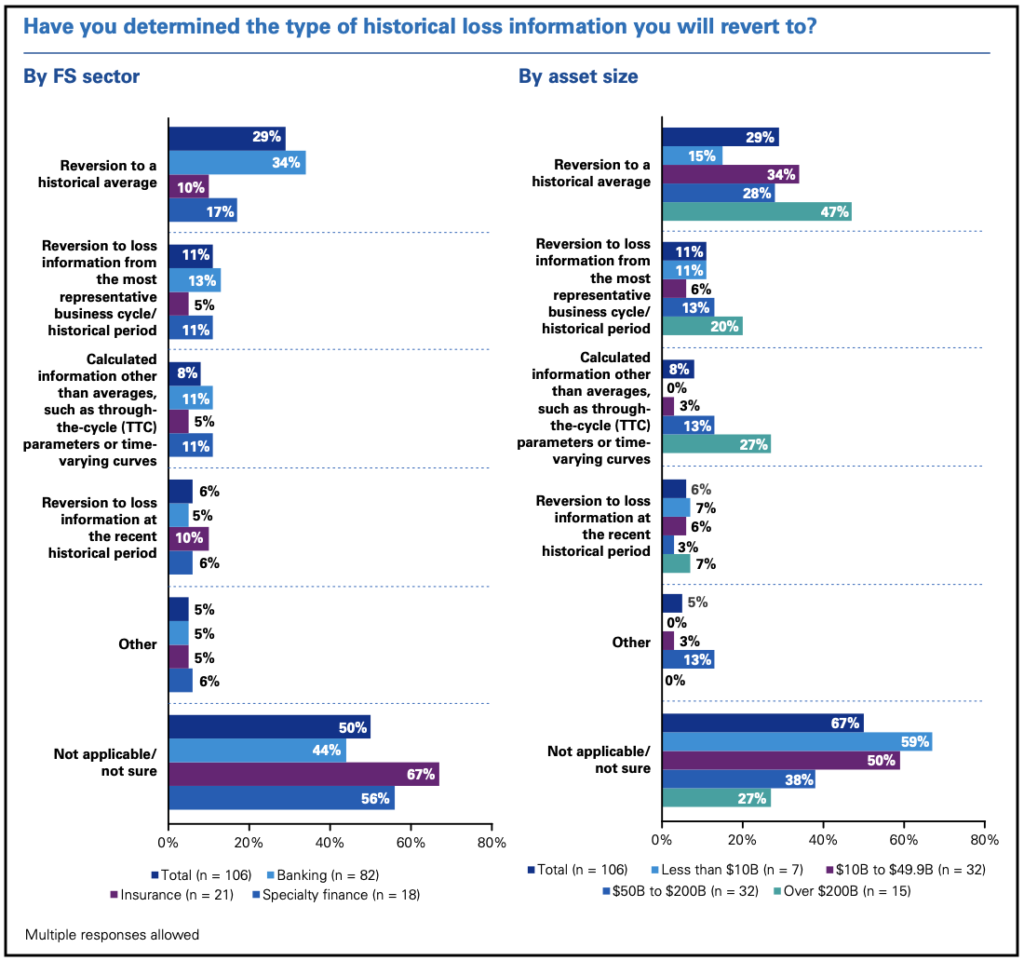

Another key modeling issue relates to how forecasts will revert to historic loss information. Sixty-six percent of banks, 81 percent of insurers, and 56 percent of specialty finance companies are still evaluating these reversion decisions. The uncertainty regarding forecast reversion is not surprising since reversion to historical data is a CECL- specific requirement.

Companies may utilize the parallel run period to gather further information to inform their forecast reversion decisions but will need to decide sufficiently in advance of implementation to ensure that these decisions are adequately captured in methodology documentation and that appropriate governance is in place.

Another important CECL-related modeling issue is how and when to use discounted cash flows (DCF) for modeling some or all portfolio segments. In 2017, 55 percent of institutions were still evaluating the use of DCFs; that figure shrunk to 39 percent this year. The decision not to use a DCF approach in modeling portfolios more than doubled from 12 percent in 2017 to 25 percent in 2018.

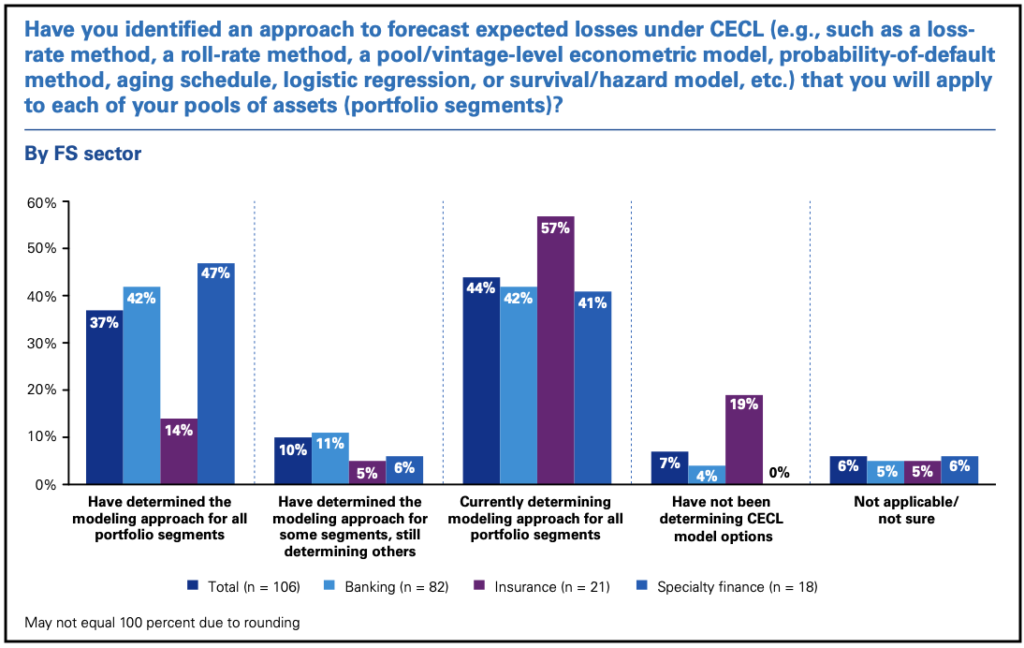

KPMG found that, on average, a significant 44 percent of institutions are still evaluating modeling approaches for all portfolios, which indicates that a portion of companies may be behind schedule. For these companies, commencement of parallel runs in early 2019 may not be feasible because modeling approaches have yet to be determined.

Forecasting future conditions

| At this critical juncture in CECL implementation, we believe financial services companies would be wise to engage with their peers and regulators to understand how other institutions are approaching discrete issues such as the reversion approach as well as myriad other modeling and accounting challenges. |

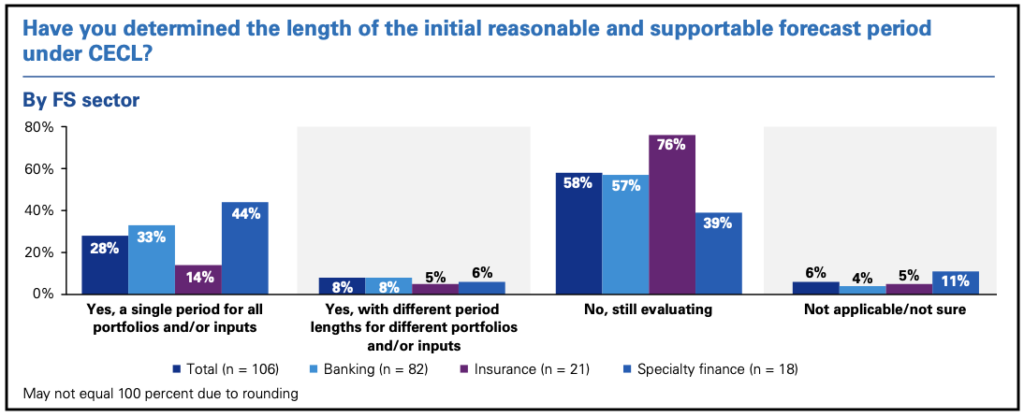

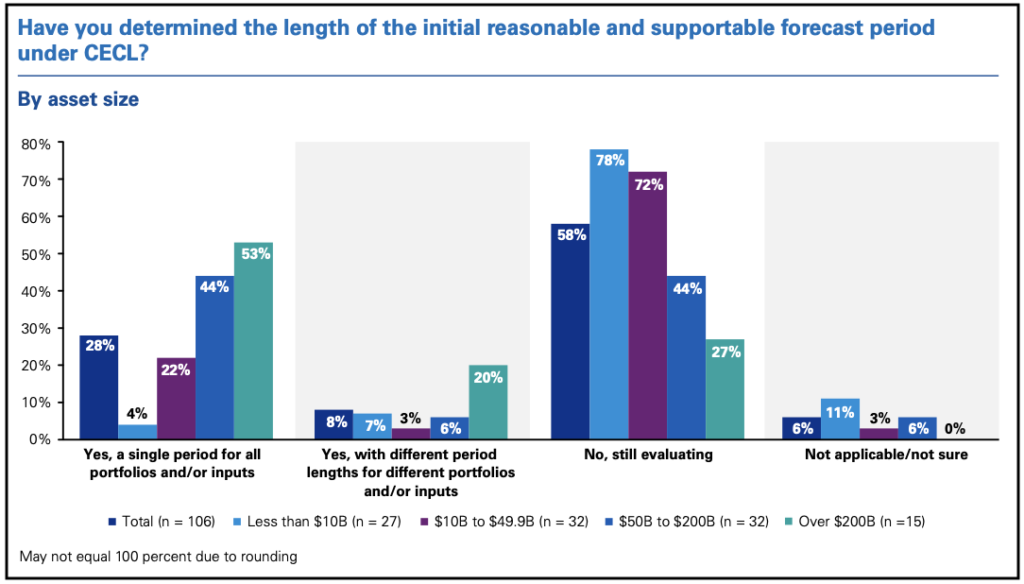

Consensus on the length of a reasonable and supportable forecast period under CECL is improving but remains elusive. Only 36 percent of institutions have made a firm determination, while 64 percent were still evaluating or unsure of what the reasonable or supportable forecast period should be. In 2017, 94 percent of institutions were still debating the reasonable and supportable forecast period; only 6 percent had made a firm determination.

The KPMG survey indicates large disparity in planned approaches to the reasonable and supportable forecast period, both in terms of actual length of the period and in terms of respondents’ plans to utilize different periods for different portfolios and/or inputs. The survey results suggest that few entities across all sectors are planning to have different reasonable and supportable forecast periods across different portfolios and/or inputs, but this intention was more prevalent for larger institutions with more than $200 billion in assets. Of the institutions planning to utilize a consistent reasonable and supportable forecast period across all portfolios, larger institutions asserted this intention more frequently than smaller institutions.

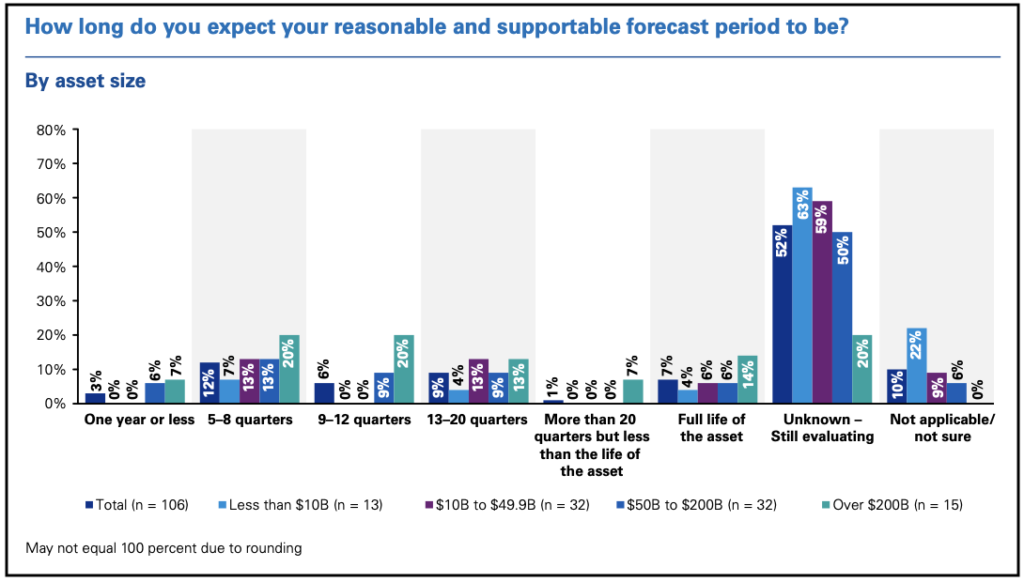

Some companies favor short timeframes of approximately one to two years, while others believe they can forecast for most or the entire life of certain instruments. And still, others believe that DFAST / CCAR practices create a presumption that the reasonable and supportable period must be at least 9 quarters. In the survey, an almost equal percentage of participants expect a reasonable and supportable forecast period of less than 9 to 12 quarters as those who expect to use a reasonable and supportable forecast period that is greater than 9 to 12 quarters.

This wide-ranging disparity has far-reaching consequences for the application of CECL, and decisions about the length of reasonable and supportable forecasting period can affect both the complexity of economic models and their sensitivity to changes in forecasted economic conditions.

The survey results indicate companies are making progress in determining the reasonable and supportable forecast period but also that most will not have made this decision in advance of their initial parallel run.

When financial institutions were asked which type of historical loss information they expect to revert to, for periods beyond the reasonable and supportable forecast period, a relatively large number, 50 percent, were not sure, or did not believe the topic was applicable (e.g., no period of historical loss information is required where the length of the reasonable and supportable period satisfies the contractual life of the financial asset). Last year, the percentage was a similar 55 percent, suggesting very little progress on this topic.

At this critical juncture in CECL implementation, we believe financial services companies would be wise to engage with their peers and regulators to understand how other institutions are approaching discrete issues such as loan loss determination techniques as well as myriad other modeling and accounting challenges. Regulators have industry-wide perspectives and can provide institutions with data around which approaches are gaining industry- wide acceptance and which assumptions and decisions constitute outlier positions.

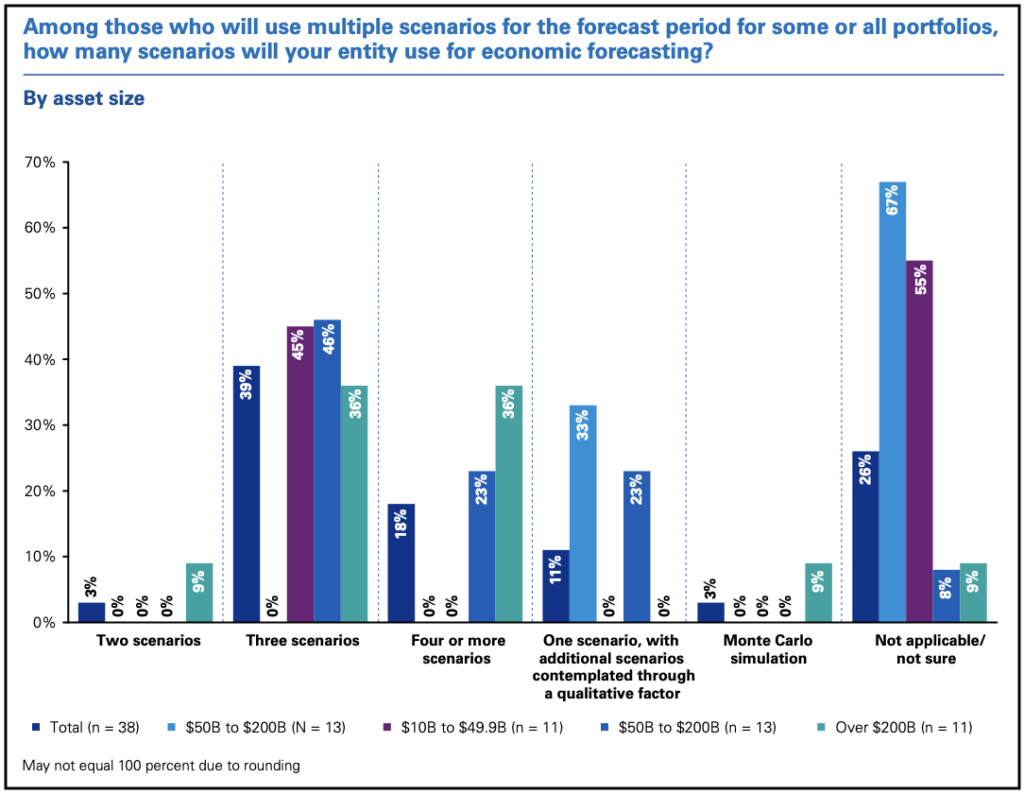

In addition, the survey revealed widespread uncertainty regarding the number of scenarios to use. Across all sectors—banking, insurance, specialty finance—just under half (44 percent) were still considering the use of multiple scenarios. Smaller institutions (under $10 billion) showed more uncertainty, and 59 percent of them are still evaluating how many scenarios to deploy. As the institution size increased, the uncertainty decreased; at institutions with assets great than $200 billion, just 20 percent were still considering whether or not they would use multiple scenarios for economic forecasting.

We anticipate that many large financial institutions will ultimately choose multiple scenarios in their forecasting. Management teams at these institutions are already using multiple scenarios for stress testing and may find that multiple scenarios provide a better estimate of expected credit losses via contemplation of tail risk.

Many financial institutions plan to conduct their economic forecasting using three scenarios that model “positive,” “negative,” and “most likely” case outcomes. This result is likely because many institutions that are subject to International Financial Reporting Standards 9 (IFRS 9) have already adopted a three-scenario approach for IFRS 9.

IT infrastructure

| Absent significant change, institutions with highly demanding reporting obligations, due in part to ALLL, may find that CECL challenges current reporting timelines. |

The wholesale shift in monitoring and reporting necessitated by CECL raises critical infrastructure issues for financial services organizations. In particular, smaller institutions, those with assets less than $50 billion, may need to adopt processes, procedures and protocols that are standard for larger organizations today. These smaller institutions need to quickly understand the human and financial capital this new infrastructure will require.

At larger institutions, one of the key challenges will be how to leverage existing IT infrastructure that has already been deployed in response to transformational regulation and rulemaking over the past 8–10 years.

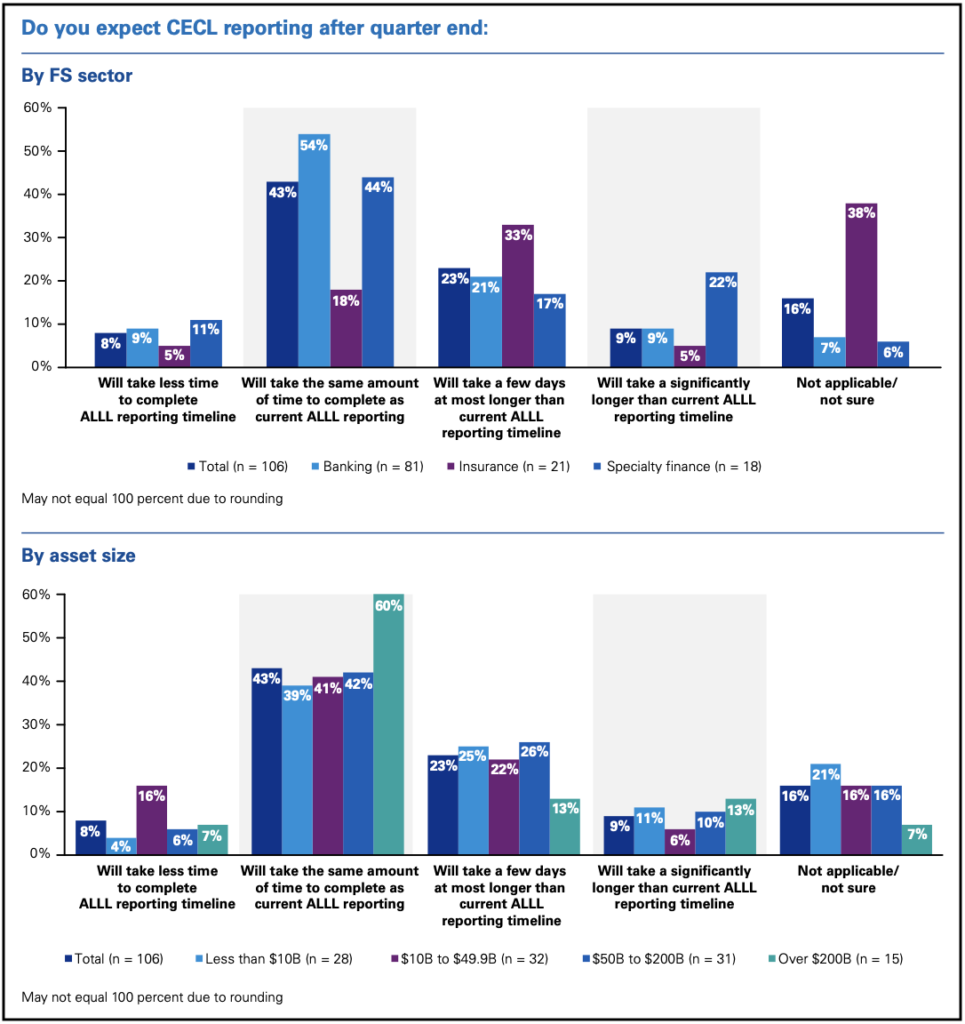

Our survey results suggest that executives at the largest financial institutions are bullish regarding the payoff they have made for prior investments in IT infrastructure. Specifically, while just 7 percent of executives at financial institutions with assets of more than $200 billion expect that CECL reporting will be quicker than ALLL reporting, 60 percent felt that it will take the same amount of time.

Executives at institutions with less than $200 billion in assets, which have likely made less investment (as many of these respondents were not previously held to the same standards under CCAR) were less optimistic. Just 40 percent believe that CECL reporting times will be the same or quicker than ALLL reporting times. KPMG believes these expectations of consistent or even quicker CECL reporting timelines may be overly optimistic since CECL is a newer requirement with much more management judgment required than ALLL reporting.

One source of optimism for timely CECL reporting is a belief among 43 percent of financial executives that the time lag on data inputs for ALLL reporting will be the same for CECL reporting. Notably, this figure has diminished over the past year. In 2017, 56 percent of institutions (among insurance companies the figure was 83 percent) felt the time lags for data inputs would be the same.

We believe the decline in the amount of respondents thinking that the data time lag will remain the same under CECL as today may be attributable to a recognition among finance and accounting personnel that the CECL estimate will likely be more volatile and take extra time to understand. Further, we feel that financial institutions may realize that an increase in the lag is inevitable to manage reporting deadlines. This should be a key concern for management. Absent significant change, institutions with highly demanding reporting obligations, due in part to ALLL, may find that CECL challenges current reporting timelines.

The survey results also indicate that many smaller institutions with assets of less than $50 billion may not yet recognize the reporting period data lag that may materialize in the CECL reporting process when compared to current ALLL reporting timelines. With ALLL, data is typically internally generated by smaller institutions and current as of the calculation date. But with CECL, forecasting is required and will usually require additional and/or external data. Just 13 percent of institutions with assets between $10 and $50 billion and 11 percent of those with assets of less than $10 billion felt that CECL time lags would be longer. This suggests that smaller institutions may not yet be focusing on this infrastructure element of the overall CECL reporting timeline.

Starting with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002, there have been numerous far-reaching financial regulations and accounting changes. While these new requirements may have initially been expensive and disruptive, our survey results suggest that for large institutions, these changes made it easier for them to comply with CECL and other requirements. Specifically, their investments in IT infrastructure and a workforce geared up to work with new requirements should make CECL adoption and implementation measurably smoother.

Data

| It appears that institutions would benefit from a gap analysis of the amount of historical data and specific elements required for CECL compared to what their data systems contain today. |

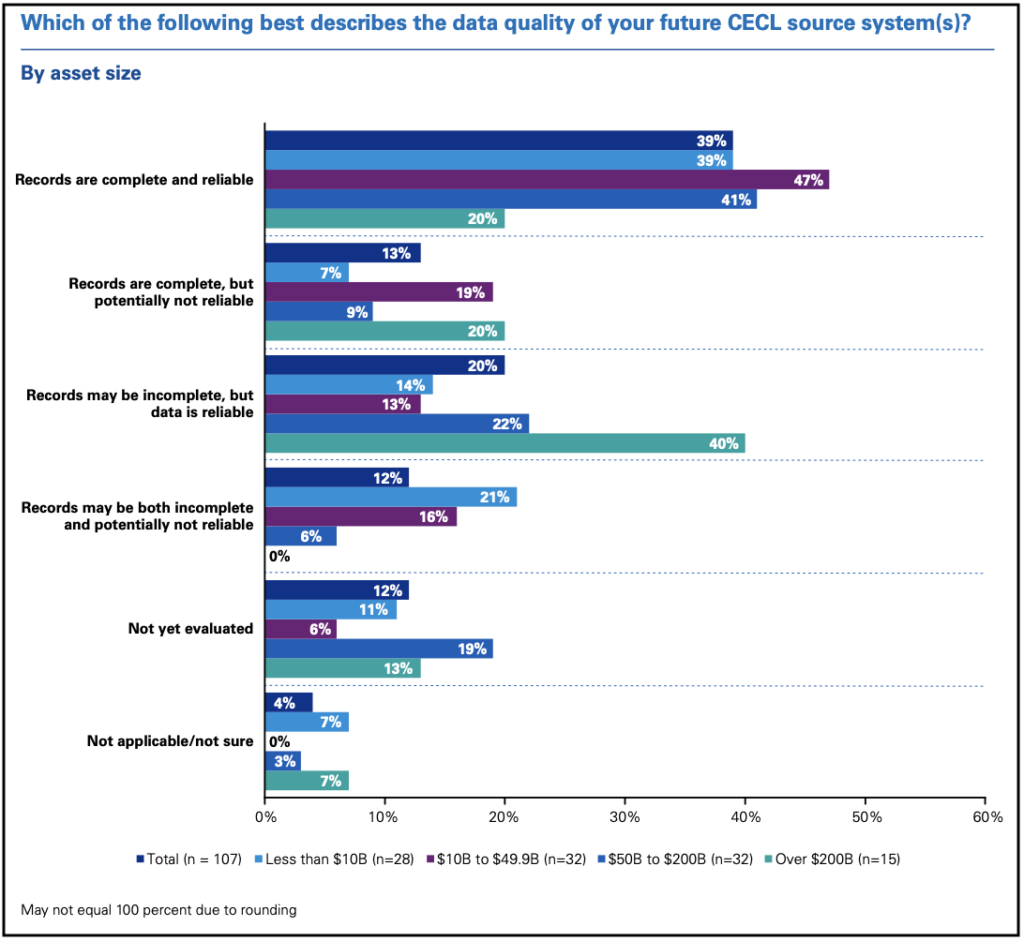

The good news with respect to data quality for CECL implementation is that 64 percent of financial institutions have undertaken significant data gathering or data quality improvement projects, and these efforts are paying off. In our 2017 survey, just 24 percent of banks, 18 percent of insurance companies, and 41 percent of specialty finance companies reported their records as complete and reliable. In the 2018 survey, 37 percent of banks, 29 percent of insurance companies, and 47 percent of specialty finance companies reported their records as complete and reliable. This represents significant progress in the past year. However, it is clear that more work needs to be done. On average, 43 percent of financial institutions indicated some form of data quality issues, and 16 percent had not yet evaluated data quality issues or were not sure of the status.

Based on these findings, it appears that institutions would benefit from a gap analysis of the amount of historical data and specific elements required for CECL compared to what their data systems contain today. Such an exercise will help quantify the expected impact and potential materiality of known issues with data completeness and accuracy. For institutions where sufficient historical data is not available, they will need to supplement data with relevant external datasets to meet CECL modeling requirements, a task that will take time, planning, and resources.

For institutions that have not engaged in data quality improvement initiatives, a starting point for addressing data quality issues would be to build a CECL data dictionary with the list of critical data elements needed for CECL accounting, modeling, and disclosure reporting along with identification of requisite controls to ensure data quality at sourcing through lineage of the CECL infrastructure.

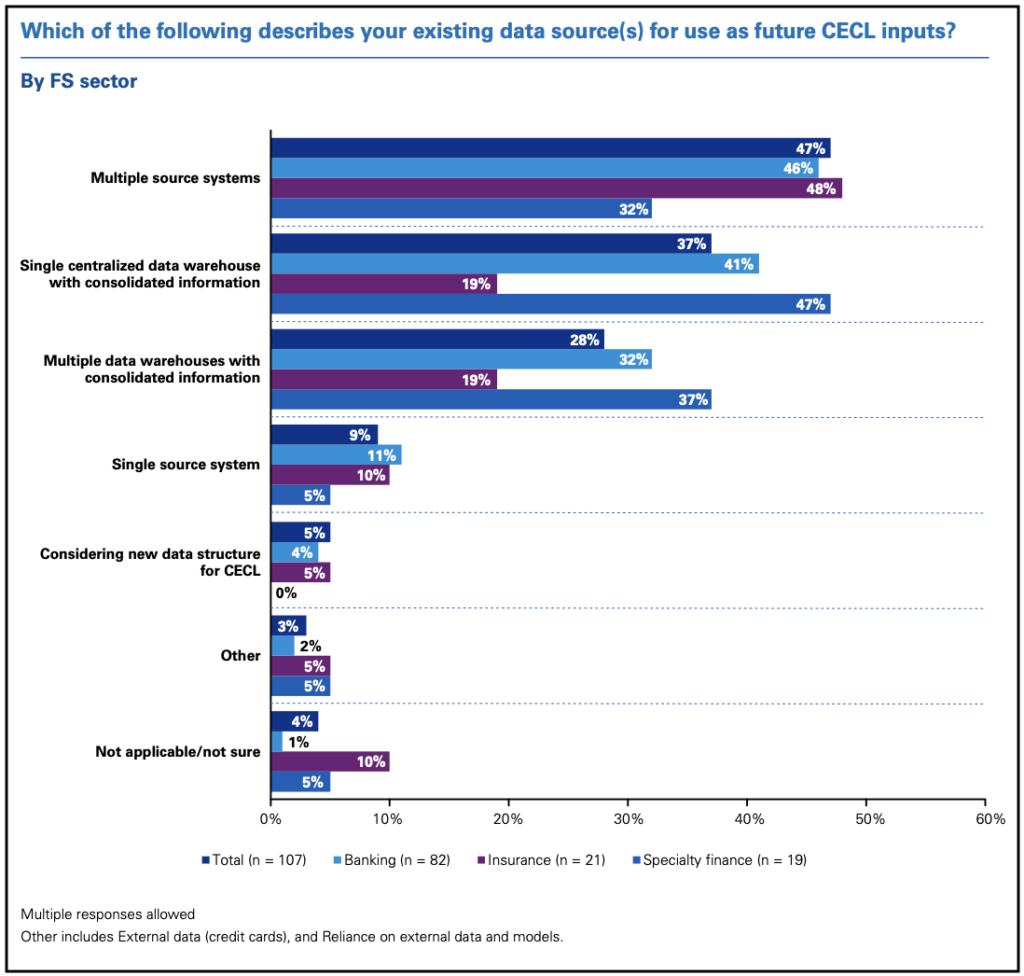

In the months following the promulgation of CECL, we noted a growing desire for a single data source. This year, 47 percent of institutions are indicating multiple source systems. But single, centralized data warehouses with consolidated information are gaining traction and being adopted by 37 percent of financial institutions. Notably, 41 percent of banks are using centralized data warehouses, and we expect that number to grow.

Companies should be aware that CECL data models will need to be reengineered to account for data integration from multiple source systems. Tools and systems supporting the data integration and consumption from either model needs to be evaluated for scalability and performance.

Governance/Internal audit

| Because CECL straddles regulatory as well as financial reporting issues, successful implementation requires effective leadership that can gain support from the entire institution. |

In our view, one of the primary challenges of CECL implementation is leadership. The human capital is in place, the technology challenge is known, and the end objective is clear. But because CECL straddles regulatory as well as financial reporting issues, successful implementation requires effective leadership that can gain support from the entire institution.

Moreover, as some institutions enter a period of extreme work compression, we believe that effective leadership will emerge as the critical driver of success. Specifically, implementation teams will require leadership that can unlock all of the resources needed to meet extremely tight implementation timelines.

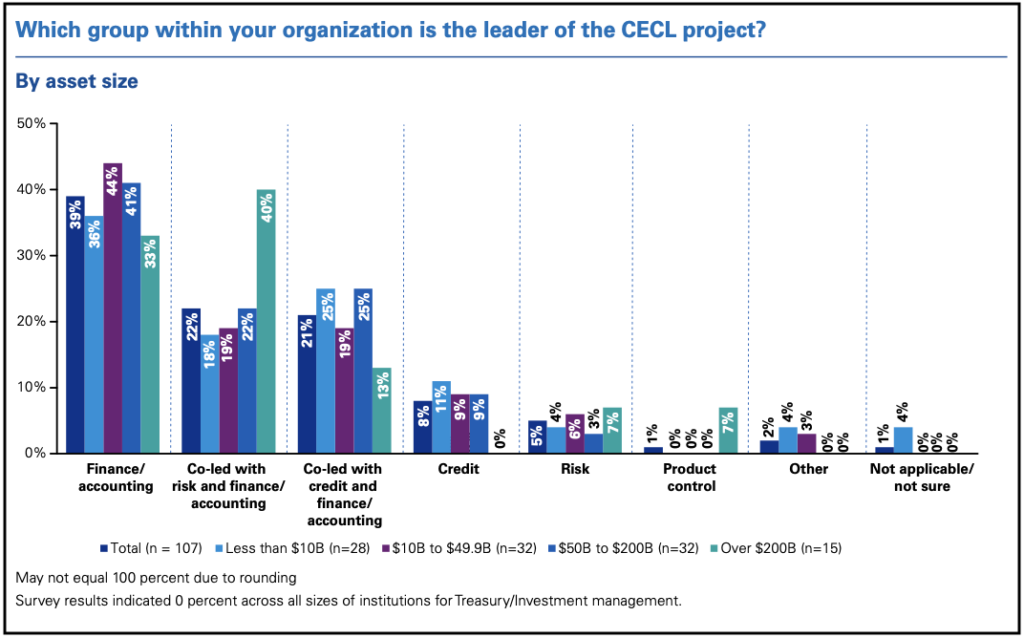

Financial institutions are increasingly adopting this view. In our 2017 survey, about 33 percent of implementations were co-led among credit, risk, and accounting; in 2018, this figure has grown to 43 percent. This shift indicates that organizations are recognizing that CECL requires not only cross-functional involvement but also cross-functional leadership across a variety of impacted functions.

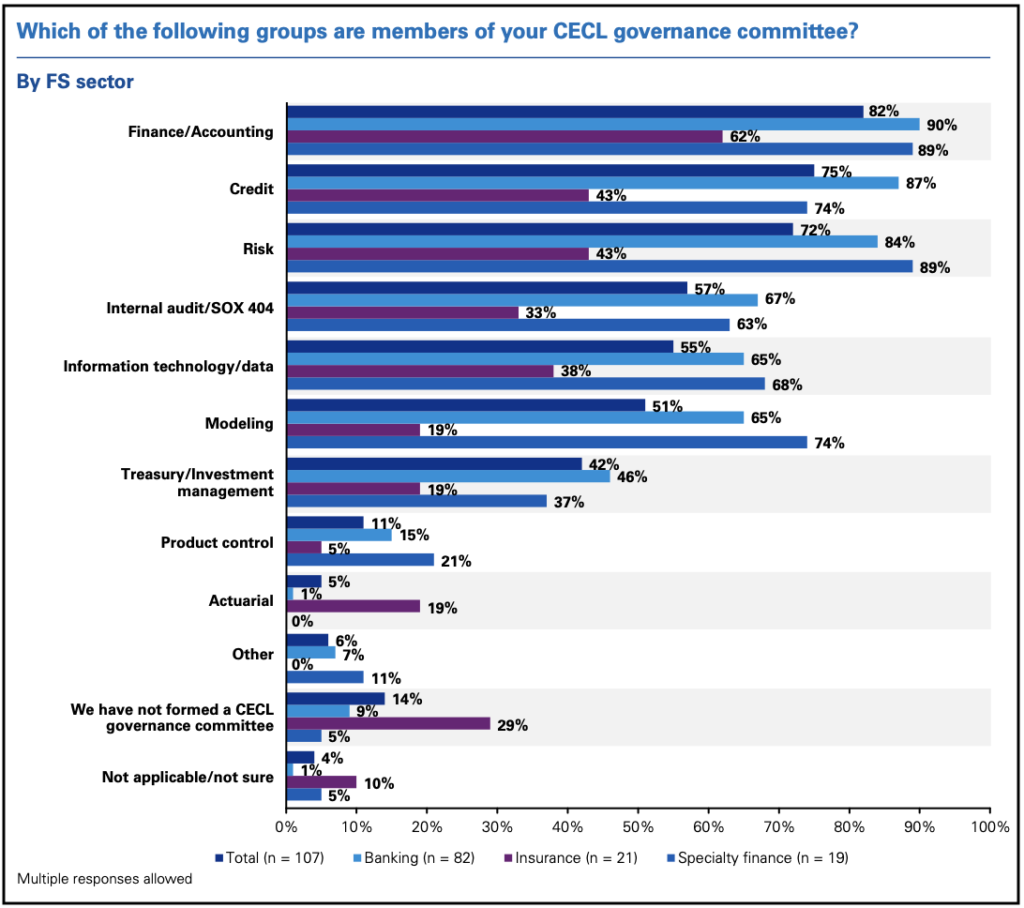

Leading up to implementation, we believe a CECL governance committee represented by risk, accounting, credit, IT, IA, modeling, and product control is important, and 86 percent of institutions have formed such a committee.

Looking at the absence of governance committees by asset size, just 21 percent of smaller institutions with less than $10 billion in assets had a governance committee. We suspect that for institutions of this size, senior management believes they have visibility throughout the institution from end to end, and that a committee would detract from the nimbleness of their implementation.

Also notable among the governance-related survey results was the growing role of internal audit (IA) in CECL implementation. Combined, IA was a member of the CECL governance committee among 38 percent of financial institutions in 2017. In our survey results this year, the figure had grown to 57 percent, and among banks the figure was 67 percent. In 2017, just 47 percent of banks had IA participation on their CECL governance committees. We suspect the growing IA participation rate may stem from the tendency to de-emphasize controls during the early stages of the change project. However, as the complexity of CECL becomes clearer to organizations, the need to have a robust understanding of internal control considerations has emerged and the value of including IA in such discussions has become more obvious.

Another key governance issue is the alignment and reconciliation of CECL forecasting assumptions and other judgments to those used in other internal and external reporting processes by the organization. For banks, where CCAR and DFAST reporting comes into play, 61 percent said they will seek to achieve alignment with these stress test reporting requirements compared to 57 percent a year ago. In addition, banks contemplating the use of one model for multiple regimes—CECL and CCAR for example—will need to design models that work with each requirement.

Alignment may produce sound results from a governance standpoint and offer lower costs. However, alignment does present additional challenges. Specifically, it will require that flexibility is built into CECL processes, and this requirement will impact the timing and degree of difficulty for implementation. Further, organizations may find mixing perspectives and purpose between financial reporting and regulatory compliance leaves them in unexplored territory, whereby regulatory compliance processes already in place may not be subject to the same degree of governance and controls that would be required for financial reporting.

Business impacts

| As CECL projects become more developed, the impacts of the new standard on operations may become a more significant issue. Similarly, CECL may affect the way executives manage regulatory capital as financial institutions look at ways to minimize some of the impacts of CECL. |

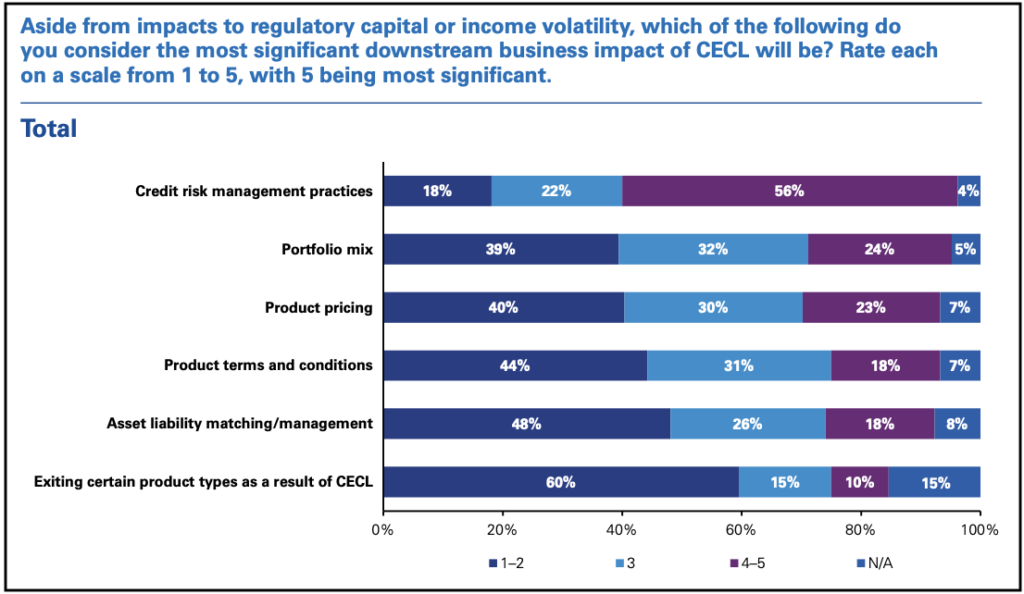

Since the passage of CECL in June of 2016, there has been persistent speculation that the new standard would influence financial institutions to reexamine the economics of certain products, leading to potential changes in pricing, lending strategy, credit risk management, or other business considerations.

However, this year’s survey reveals a contrary result. For 60 percent of institutions, CECL was not a major concern when determining their product mix. Specialty finance companies that hold more unique and riskier product portfolios were more affected, and 37 percent said that CECL would have a “moderate” effect on their product portfolio. In general, rather than abandoning product lines, it appears that financial institutions are optimistic they can make CECL work with their current portfolio mix.

The greatest concern among executives appears to be the impact of CECL on regulatory capital. We believe that this is principally driven by uncertainty as to whether there will be a regulatory response to CECL in the form of capital relief and, if there is, exactly what form that change will take. Banks appear to be concerned about this impact and are pushing for alternative CECL options to alleviate the risk to capital.

However, banks do not have many options at this point in time. Once institutions have begun CECL reporting and have a better understanding of the regulatory environment, strategies for managing the impact on regulatory capital will become more apparent.

In our survey last year, we noted that changes in product pricing, terms and conditions, and asset and liability management would come into focus as institutions moved closer to implementation. Responses to our 2018 survey largely demonstrated the same level of concern regarding these issues as they did in 2017.

For instance, in 2017, 40 percent of financial institutions felt the impact of CECL on product pricing was of little concern, the exact same percentage in 2018.

We would urge financial institutions to keep these impacts in mind as the implementation deadline approaches. As CECL projects become more developed, pricing may become a more significant concern. Similarly, CECL may affect the underlying terms of financial products or the asset mix on the balance sheet as financial institutions look at ways to minimize these impacts. At this stage, it’s understandable that executives are more focused on the accounting and modeling decisions that must be made before CECL adoption.

However, other business impacts will also need to be considered. Once CECL is adopted, there will be more data available with regard to the expected allowance for credit losses in a given economic environment and related capital impacts. Once these are known, this is likely to flow into market pricing and product structures.

Also notable among the results was an apparent dichotomy in thinking between credit risk personnel and finance/ accounting personnel. In almost every downstream business impact contemplated in the survey—portfolio mix, product pricing, and product terms and conditions, a higher percentage of credit personnel ranked the impacts of CECL to be significant compared with assessment of impact by accounting/finance personnel. This was true in the 2017 survey as well. Further, the percentages for each impact remain largely the same. We suspect that for these individuals, contemplation of second-order impacts may very well have taken a back seat to critical CECL decisions that need to be made in order to commence parallel run activities in 2019. It is likely that contemplation of such second-order impacts will recommence as adoption draws nearer. It is critical that management leading the accounting change communicate the company’s perspective and implementation plan to all relevant functions to set the tone from the top.