Analysts and investment managers always need to understand the full story of the companies in which they’re looking to invest – and that’s especially true when incorporating material environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors into investment decisions and investment selection. Specifically, managers need to understand whether there are material risks or opportunities tied up in ESG factors that don’t appear on a balance sheet or income statement.

Increasingly, ESG factors cannot be dismissed as immaterial. For example:

Governance: In February 2019, Kraft Heinz announced a $15.4 billion write down for two of its key brands. The sponsor of an ETF (exchange traded fund) explained that they avoided including Kraft Heinz in their fund chiefly because of its governance score, citing limited independent board membership.

Social: Tesla faces a variety of racial harassment and hostility lawsuits following incidents at its Fremont California assembly facility. One federal trial is scheduled to commence in 2019 as the company faces intense scrutiny over its governance practices following a settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Environmental: After the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, British Petroleum pled guilty to 11 counts of manslaughter, 2 misdemeanors, and a felony count of lying to Congress. Ultimately, the criminal and civil proceedings cost approximately $42 billion.

Materiality will differ from sector to sector, industry to industry. All companies need to have good corporate governance, but environmental or social factors are often unique to an industry or sector.

There is also a ‘demand pull’ aspect to the incorporation of ESG standards into investment analysis. That is, investment managers are accountable to a variety of constituents — employees, customers, investment committees, investors, and other stakeholders — who increasingly want ESG standards reflected in pension, endowment, mutual fund and index fund investments. In this regard, it doesn’t matter what an investment manager thinks is material as long as their customer does.

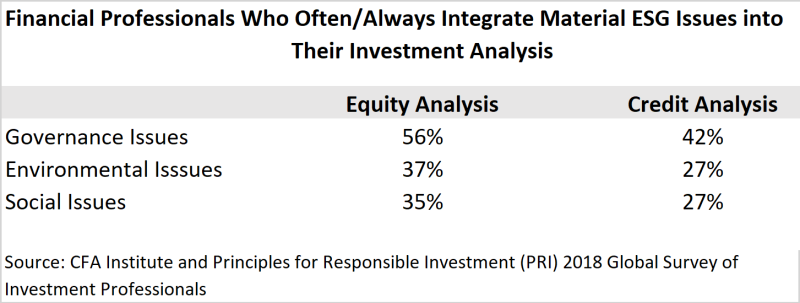

Regardless of the source of the motivation, the chart below shows that ESG integration is gaining traction.

But the question becomes: how do investment managers incorporate ESG into what are well-developed analytical protocols? Despite widespread use, the quantitative and qualitative integration of ESG standards into traditional investment analysis is in its infancy. Nonetheless, it is being practiced around the globe.

The CFA Institute and Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) set out to establish the best practices for integration as they now exist and are being practiced through surveys of 1,100 financial professionals and 23 workshops in 17 investment centers around the world. What follows is a summary of the qualitative and quantitative integration of ESG factors into traditional investment analysis.

Qualitative Adaptation

In its nascent history, ESG integration was commonly implemented with qualitative approaches. However, with the amount of ESG data proliferating, practitioners are now integrating ESG factors in a more quantitative manner. Regardless, qualitative integration remains popular. Here are some examples:

- The ESG analysis can be the deciding factor between otherwise identical companies or countries. If all other factors are equal, the practitioner often chooses the company or country that performs better on its ESG analysis.

- If a company has a low score/assessment on certain ESG factors, engagement with the company — a common occurrence in fundamental analysis — can improve those factors, perhaps resulting in a buy/hold decision.

- Practitioners invest in undervalued securities that have an opportunity to outperform based on improving ESG performance and divest from overvalued securities that could underperform based on deteriorating ESG performance.

- The ESG analysis of a company or country is studied alongside the fundamental investment analysis of that company or country to inform a “buy/sell/hold/don’t invest” decision. If the company or country is viewed poorly based on its ESG performance and on its valuation assessment, it could lead to a “sell” or “don’t invest” signal. If the same company or country is rated poorly on its ESG performance but well on its valuation assessment, it could lead to a deeper analysis of the company or country before a decision is made.

Quantitative Approaches

The increasing availability of ESG data from companies, third parties, governments and primary research offers the opportunity for rating and ranking analysis of the data, as well as observing trends and the ability to make ‘apples to apples’ comparisons. These advances have led to the quantitative application of ESG standards in investment analysis and decision making.

Some examples of practitioner use of quantitative analysis of ESG issues to inform investment decisions include the following:

- ESG analysis of a company or country leads to an adjustment of its internal credit assessment based on anticipated capital expenditures needed to remain in or achieve compliance with shifting or intensifying ESG regulation or the expected value of legal exposures based on compliance gaps in any of the ESG factors.

- A sensitivity analysis showing how ESG scores move in relationship to other financial variables leads to upward/downward adjustments to forecasted financials, valuation-model variables, valuation multiples, forecasted financial ratios, and/or portfolio weightings.

- ESG data/analysis is included alongside other fundamental and market data points in a quantitative model that drives portfolio construction decisions. For example, a global industrial ETF might preclude companies with carbon emissions above a certain threshold.

- Statistical techniques are used to identify the relationship between ESG scores and price movements and/or company fundamentals. This can result in systematic rules for portfolio-weighting recommendations.

- The estimate of a bond’s price fluctuation with market movements (its Beta) is adjusted for ESG risk. Because of stringent standards maintained by a fund, which may include Beta ranges, the amount of the bonds investors are able to hold in their portfolios could be more/less than previously calculated.

What the above examples illustrate, but may be hard to appreciate on the first pass, is that the adoption of ESG factors in a quantitative fashion has led to their incorporation among so called “passive” asset managers. These are managers that build and adjust portfolios based on rules and metrics rather than the judgements that active managers rely upon to select securities. For instance, an exchange traded fund or ETF might consist of semiconductor companies with market capitalizations of $10 billion or more. When a constituent company falls below a $10 billion market value, it is sold and removed from the ETF. Similarly, an S&P 500 Index Fund, which owns, in proportion, each of the 500 companies, will adjust when new companies are removed from the index to make room for news ones. In both of these examples, the buy/sell decisions are “passive.”

The reason this is important is that the investment management business is moving — perhaps inexorably — toward passive investment strategies. They are dramatically less expensive, and according to at least one very vocal camp, they perform the same or better than actively managed portfolios. In 2008, passively managed assets amounted to about $700 billion. In 2018, the figure was almost $4 trillion, which represented almost half of all equity assets in the United States.

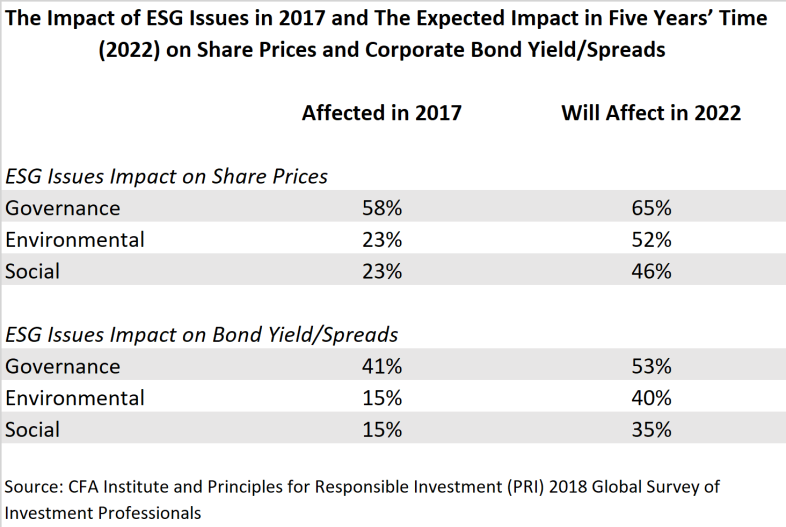

As a result, the ability to assimilate ESG data into passive investment strategies means ESG can exert influence across the entire spectrum of investment analysis and securities selection. Clearly, as the above chart demonstrates, the financial services industry is poised to further embrace ESG standards. The good news is that to the degree companies want to make themselves attractive to all types of investors — active as well as passive — they will need to adhere not just to financial standards, but ESG standards as well.